Movement as medicine

Shirley Sahrmann, BS ’58, MA ’71, PhD ’73, PT, FAPTA

By Ginger O’Donnell

At age 88, Professor Emerita of Physical Therapy Shirley Sahrmann, BS ’58, MA ’71, PhD ’73, PT, FAPTA, is still as passionate about advancing the field as she was when she joined the WashU faculty in 1961. Now retired, the revered educator of more than five decades — whose scholarship has shaped what it means to practice physical therapy today — continues to advocate for the role of movement in preventing illness and fostering healthier lives. This summer, she led a virtual continuing education course for more than two dozen physical therapists in Japan and an on-site course for 12 Japanese physical therapists. And she recently delivered two lectures to the MLB’s Arizona Diamondbacks about optimal movement of the shoulder and hip to prevent injury.

“I truly believe that if physical therapists do their job well at guiding movement, we can further the age before people develop major health problems,” she says. “The best analogy is dentistry. Shortly after getting your teeth, you go to a dentist. And then you go regularly. The vision is that we’d start movement exams early in life to monitor young children on a yearly basis.”

This was not the enlightened approach when Sahrmann entered the university. She came to WashU in the mid-1950s, roughly 10 years after the physical therapy program transitioned to a baccalaureate degree as part of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. It had initially launched in 1942 as a six-month training course for treating injured soldiers during World War II. At the time, physical therapy was gaining national attention for its capacity to treat polio, a motivator for Sahrmann alongside her passion for physical activity — she relished playing softball, basketball, volleyball, and other sports. But the field was still in its infancy. “When I started, there were three faculty and 18 students,” she recalls.

“They are superstars — so bright and committed. That was one of the advantages of starting a PhD program. Now we have people who build on that foundation by becoming lead investigators in the profession.”

Shirley Sahrmann, BS ’58, MA ’71, PhD ’73, PT, FAPTA

Sahrmann threw herself wholeheartedly into the profession, commencing an evolution that continues to this day. Ten years after becoming a WashU professor of physical therapy, she developed an interest in stroke patients. She went back to school at WashU Medicine to deepen her expertise in this area, earning both a master’s degree and a doctorate in neurobiology. There, she built a close relationship with the late Bill Landau, head of the Department of Neurology for more than two decades and one of the longest-serving faculty members at the medical school.

Together, Sahrmann and Landau conducted research with monkeys to explore movement problems in stroke survivors, using the analog methods of the day, such as recording brain activity during movement on strip chart cords. “That part of my life, I spent more time with monkeys than people,” Sahrmann says. “You had to go in every day of the week — Christmas, New Years, whatever — and record and take care of them.”

Her most profound impact, however, was moving the field itself — urging it toward preventative medicine through more organized, consistent diagnostic standards and a greater emphasis on research. She developed a theoretical framework known as “the movement system,” which was adopted by the American Physical Therapy Association in 2013 as the foundation for the profession, entered into Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, and centered at various national and international conferences, notwithstanding its influence on WashU’s No. 1 ranked program.

“Like the immune system, the movement system is a system of systems,” Sahrmann explains. “It incorporates the musculoskeletal system, the nervous system, and others. How do they all work together to produce movement? That’s what it’s all about.” Her seminal 2000 textbook Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, which was later translated into seven languages, codified this new framework for generations of students across the globe.

Sahrmann would go on to help launch WashU’s PhD in Movement Science program and serve as its inaugural director. She also was the physical therapy program’s associate director of research. In these roles, she leveraged the university’s excellence across disciplines, e.g., biology, psychology, and neurology — as well as the university’s renowned strengths in interdisciplinary collaboration — to build a robust research culture. “We created the doctoral program to examine the evidence for what we were doing,” she says. “Not just to do things, but to know things.”

Her tenacity laid the foundation for today’s research powerhouse, home to several graduates of the PhD in Movement Science program who are now pursuing their own groundbreaking scholarship as WashU faculty members. This includes program Director Gammon Earhart, PhD ’00, PT, FAPTA, whose research focuses on the role of movement in Parkinson’s and other neurological and neurodegenerative diseases, and Catherine Lang, PhD ’01, PT, FASNR, FAPTA, who explores effective and efficient rehabilitation for stroke survivors and people with various neurological and neurodevelopmental conditions.

“WashU was so wonderful to me. Attending this university was one of the most fortunate decisions I’ve ever made. I’ve had all this opportunity with clinical practice, education, etc. How could I not want to return that?”

Shirley Sahrmann, BS ’58, MA ’71, PhD ’73, PT, FAPTA

“They are superstars — so bright and committed,” Sahrmann says. “That was one of the advantages of starting a PhD program. Now we have people who build on that foundation by becoming lead investigators in the profession.”

Looking back, Sahrmann marvels at the WashU physical therapy program’s progress in integrating research, education, and clinical care, and achieving excellence in each. “That’s the strength of the WashU program today,” she says. “It does all three things in a remarkable way. You have leading researchers in the profession. You have a clinical practice that is growing. And you have faculty who participate in the clinical practice. It all goes hand in hand.”

From her current vantage point as an alumna and professor emerita, Sahrmann now continues her loyalty by investing in the program’s excellence through philanthropy. Throughout her industrious, boots-on-the-ground career, she has amassed enough savings to fund five endowed scholarships, among other gifts. She believes strongly in reducing financial burdens for students and making a physical therapy education accessible for all qualified applicants.

For her, WashU remains the gift. “WashU was so wonderful to me,” she says. “Attending this university was one of the most fortunate decisions I’ve ever made. I’ve had all this opportunity with clinical practice, education, etc. How could I not want to return that?”

From WashU to DARPA

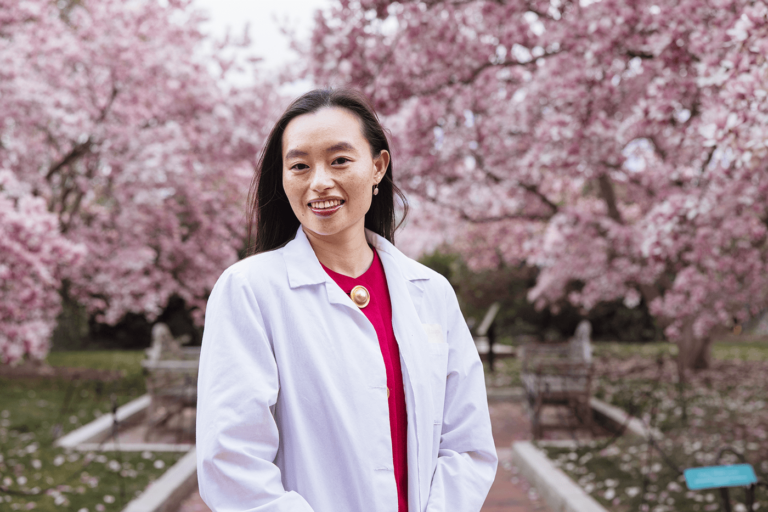

In her first year of high school, Alissa Ling, AB ’18, started volunteering more than 10 hours a week at Walter Reed Military Medical Center. There, she first learned about emerging rehabilitation devices — like brain-controlled prosthetic arms — that offered soldier amputees a rare and vital return to mobility.

Expert hands, timely hope

WashU Medicine’s Taylor Family Department of Neurosurgery is home to the latest innovations in neurosurgery and neurotechnology to address complex brain tumors. Eric C. Leuthardt, MD, performed a groundbreaking, minimally invasive procedure in 2010.

A new era in mental health research

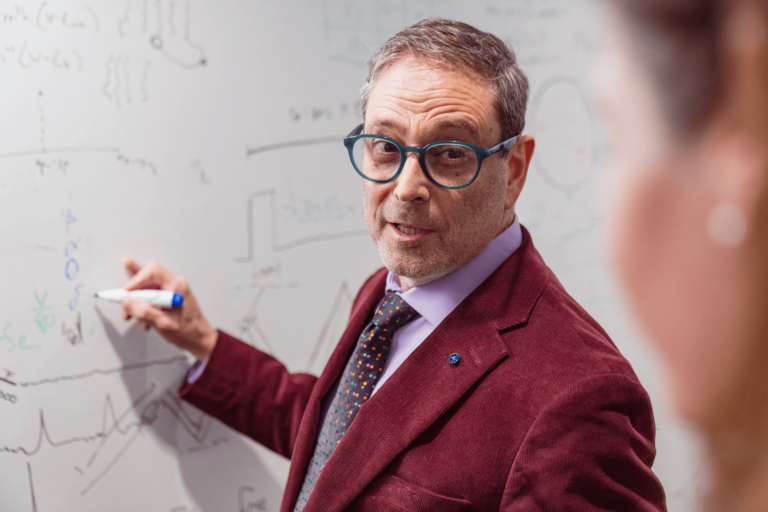

Eric Lenze, BA ’90, MD ’94, leads the Department of Psychiatry at WashU Medicine, which has a long history of international excellence in research, education, and patient care.

The healing power of neuroscience

Physician-scientist Michael Avidan, MBBCh, leads WashU Medicine’s Department of Anesthesiology, a world leader in anesthesiology research, education, and patient care.